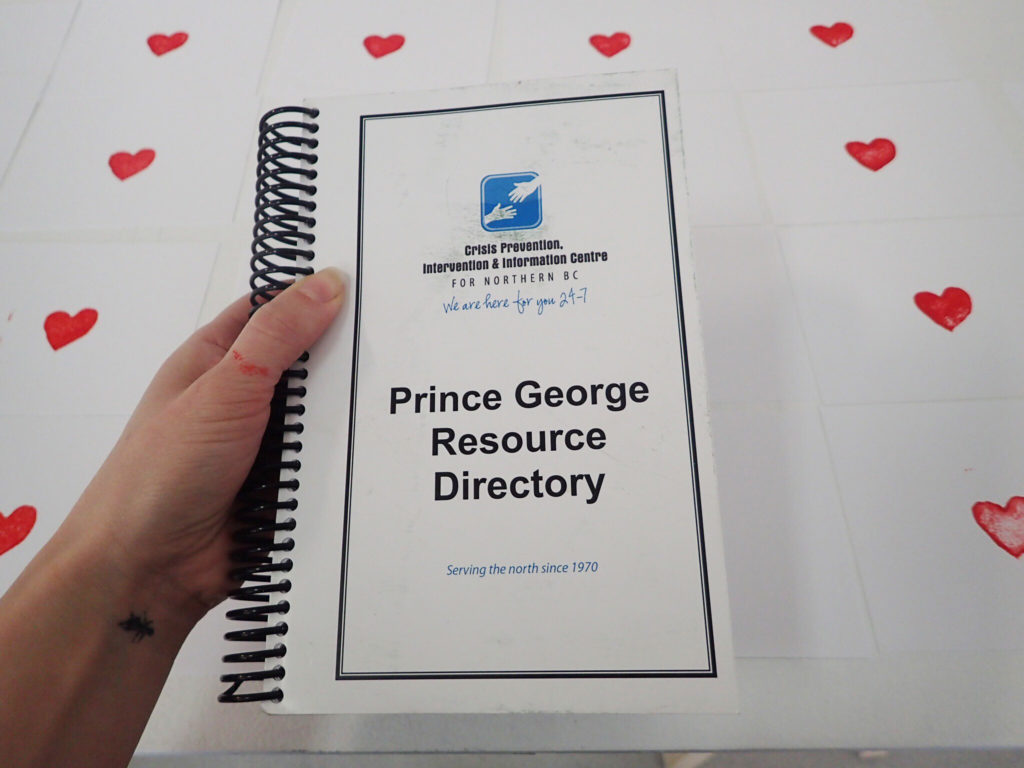

The month of April marks the final artist residency for the Neighbourhood Time Exchange | Downtown Prince George. Concluding the program is artist Frances Gobbi, who is also a long-time Prince George local. While many of the other artists-in-residence came from away, Gobbi’s personal relationship to the city offers a uniquely considered perspective of the place. In a conversation with the artist, she noted that even in a few short weeks, the residency is offering her the time and the opportunity to deepen the ties she has with her community. Gobbi has been diving into her personal studio practice, hosting public workshops, and working with Downtown Prince George and the City of Prince George on a co-partnered project that looks specifically at public mural practices in the downtown.

As an artist and educator, Gobbi sees art-making as a problem-solving activity that has wide reaching implications. Offering new perspectives to look at the world, art has the capacity to impact many other aspects of our lives. What tools can help us process things we don’t immediately understand? How can we be critical and engaged in the world? How can we develop strategies for thinking creatively? How do we measure our capacity to create? As Gobbi notes, the role that art can play in the field of education, in the development of communities, and in the personal lives of those who engage with the arts, is multifaceted and complex.

Working in the studio on pushing her artistic practice, Gobbi is developing an ambitious watercolour project. With the goal of producing a quilted wall-based installation, she will be extending her interests in abstraction, formalism and systems studies. Her watercolours are often started on a gridded pattern base, which are then carefully altered through a number of diverging and intersecting lines. The resulting watercolours depict a series of interlocking, but distinct, polygonal and circular shapes. Over the past several years, the artist has produced a long-standing investigation into the way rules, structures, or forms act as scaffolding from which to look at the way representations operate on the picture plane. Historically, abstraction has carried a moral dimension, one that seeks simplicity or purity, and it can be a highly symbolic practice. Gobbi earnestly works within this framework, using her visual language to move beyond the vernacular and into spiritual and conceptual realms.

Already, the artist has been generously sharing her skills and expertise on this artistic style through a number of workshops that have been open to the public. Collaboration and dialogue are important aspects of the Gobbi’s process, and she notes the incredible reciprocity and mutual learning that can happen when communities create together. Sharing the challenges of an exercise, or witnessing the number of ways that different people can interpret the same prompt, is a source of constant inspiration for the artist. Shapes, colours and forms are expressive tools that are infinitely malleable.